By Richard Joyce, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

As lightning bug season warms up in the more southern parts of the United States, firefly experts and aficionados feel excited, but also a bit frantic. The adult flight period of most firefly species lasts just a matter of weeks, and the phrase that often comes to mind is, so many sites, so few nights! Each year we are presented with brief windows of opportunity to learn more about firefly species, but too often we’re constrained by the lack of person power to head out into the night to survey.

This year, I am optimistic that Firefly Atlas participants (yes, you!) will make great strides in expanding and updating our knowledge of North American Lampyridae. Read on for an overview of the types of discoveries we could make.

Fill gaps in distribution maps (and seasonal calendars) for threatened species.

Florida intertidal firefly in the Indian River Lagoon

Despite having one of the largest expanses of mangrove and saltmarsh habitat on the eastern coast of Florida, the Indian River Lagoon has surprisingly few records of the Florida intertidal firefly (Micronaspis floridana). Where are the remaining populations in this environmentally-stressed estuary? This May would be a great time to survey, but this adults and larvae of this species can be found during most of the year.

LINK: Florida intertidal firefly (Micronaspis floridana)

Keel-necked firefly in the Chesapeake Bay

Just last year, surveyors with Maryland Biodiversity project found keel-necked fireflies (Pyractomena ecostata) on the Eastern Shore of Maryland for the first time. What is this species’ distribution in the Chesapeake Bay? Is it on the Western Shore? We’ll need more Firefly Atlas participants surveying salt marshes on July nights to answer this question.

Cypress firefly in Kentucky?

Photuris walldoxeyi is known to occur in high quality swamp habitats from Mississippi north to near Bloomington, Indiana, but it’s never been found in Kentucky. Does Kentucky have cypress firefly populations? Someone should go check between mid-May and mid-June!

LINK: Fireflyexperience.org

Check out our Wanted Posters for some other ideas of species to look for!

LINK: Wanted Posters

Get to know them all! Make a dent in data-deficiency.

In 2021, conservation assessments of North American firefly species found that over half of assessed species were data-deficient, meaning that we simply didn’t have enough current information about their distributions, trends or threats to know how they are doing.

LINK: Conservation assessments of North American firefly species

Below are a few examples of data-deficient firefly species that are just waiting to be studied.

Cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis)

Historically, this lightning bug had a widespread range across North America, from Florida north to Ontario and as far west as Oklahoma. However it’s unclear what its current range is, and as a wetland specialist it can’t live just anywhere. It was found to be data-deficient in the 2020 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species assessments. Mapping out current populations will be the first step toward better understanding the conservation status of the cattail flash-train firefly.

LINK: It was found to be data-deficient

Punctate firefly (Photinus punctulatus)

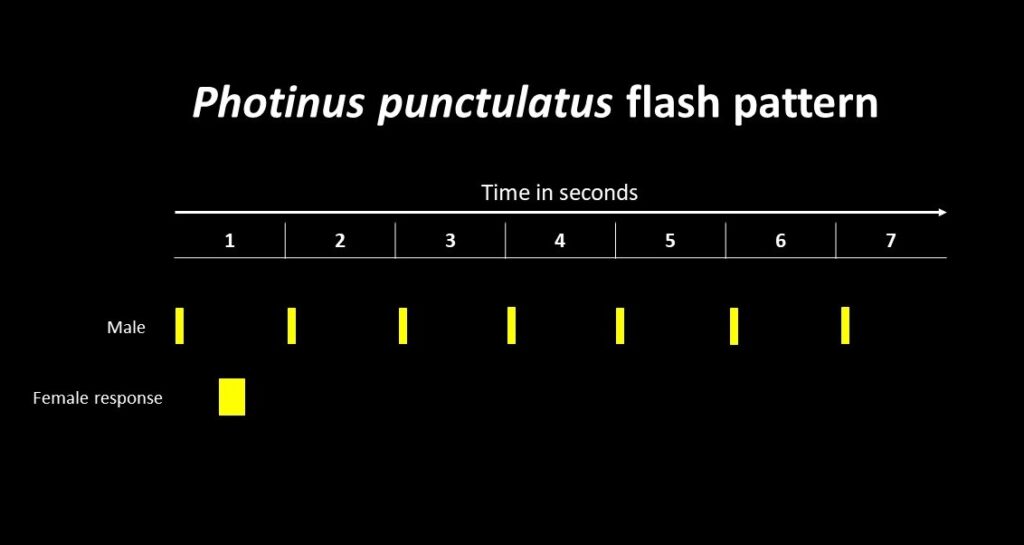

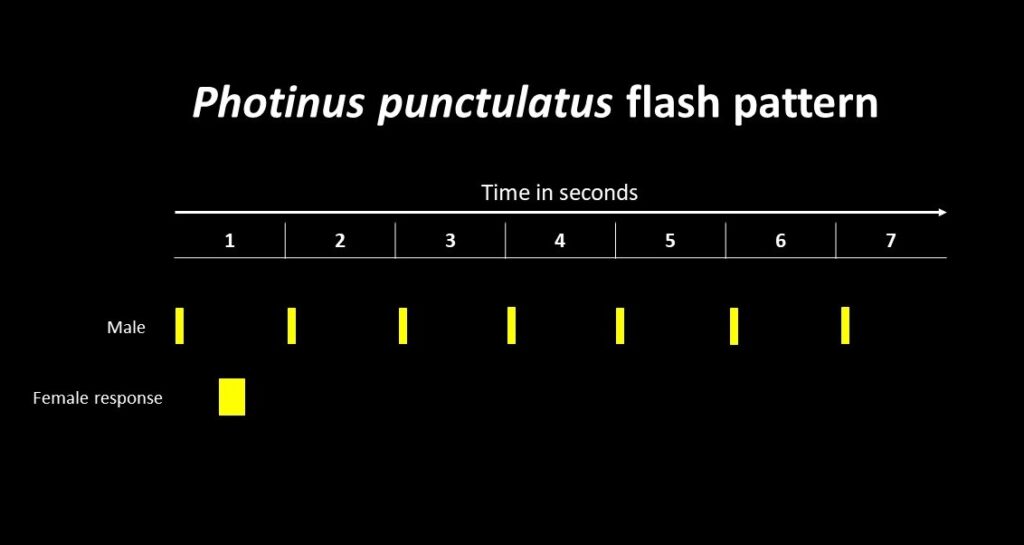

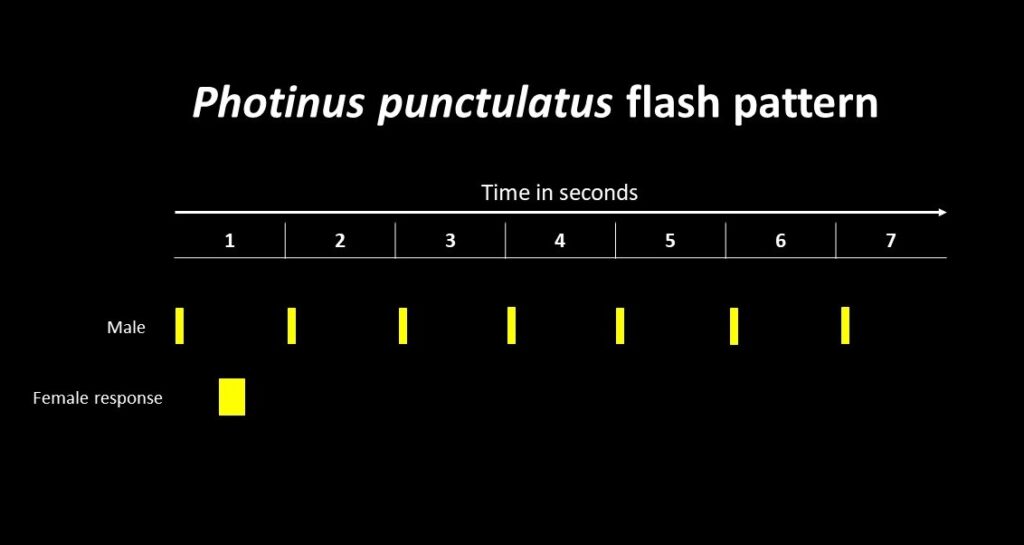

Named for the pitted texture of its pronotum (headshield), Photinus punctulatus is a species in which the females are brachypterous (short-winged) and unable to fly. This means that if they were to be wiped out in an area, it would be very hard for a population to re-establish itself. There are records of this lightning bug from Texas north to Iowa and Illinois, but no one has paid this lightning bug much attention in a long time! Over sixty years ago, Dr. Jim Lloyd observed Photinus punctulatus near New Salem State Historic Site in Petersburg, IL. Is the species still there? Someone should find out!

LINK: Found in a remnant prairie in Iowa

LINK: Photo

LINK: CC BY-NC

LINK: Lloyd 1966

Microphotus glow-worm fireflies of the Southwest

Tiny and mysterious, Microphotus glow-worm fireflies manage to live in harsh, arid environments in the southwestern United States. During the summer, glowing flightless females may be spotted on low perches near their burrows and males occasionally show up at moth lights. We know very little about these insects, and five of the six Microphotus species are considered data-deficient.

LINK: Photo

LINK: Some rights reserved

LINK: Photo

LINK: Some rights reserved

Wondering what data-deficient species are in your area? Use this species checklist, entering “DD” under Red List Category and selecting your state under Distribution.

LINK: Species checklist

Help us get better at counting lightning bugs

Counting fireflies or estimating their abundance can feel like an impossible task. This has made it difficult for scientists to study trends in firefly populations and to measure the response of fireflies to stressors (like pesticides and light pollution) and land management activities (prescribed fire, vegetation management, and habitat restoration).

If you are a land manager or biologist interested in monitoring a firefly population that you manage, we could use your help testing firefly index of abundance protocols. This might look like taking a series of long-exposure photographs of firefly displays, doing transect counts of glowing firefly larvae, or setting out glowing LED traps to capture (and then release) male glow-worm fireflies.

Please reach out to Richard and Candace at [email protected] if you’d like to test and refine firefly counting techniques.

Enjoy the magic!

We hope you have a fantastic lightning bug season with lots of learning and moments of awe. Thank you for contributing to our collective knowledge of fireflies and to their conservation.

Remember, the Firefly Atlas has several resources that you can turn to as you become your area’s local firefly expert:

LINK: Survey and data-entry training video

LINK: Fact-sheets for threatened species

LINK: Filterable checklist of firefly species

LINK: Participant handbook

LINK: Field guides, keys and Xerces Society firefly conservation publications

Notice: Below is a list of 20 important links included on this page.

1. Florida intertidal firefly (Micronaspis floridana)

5. Conservation assessments of North American firefly species

6. It was found to be data-deficient

7. Found in a remnant prairie in Iowa

8. Photo

9. CC BY-NC

10. Lloyd 1966

11. Photo

13. Photo

16. Survey and data-entry training video

17. Fact-sheets for threatened species

18. Filterable checklist of firefly species

20. Field guides, keys and Xerces Society firefly conservation publications

Please note that while screen readers have made significant strides, they may still lack full support for optimal web accessibility.

By Richard Joyce, Endangered Species Conservation Biologist

As lightning bug season warms up in the more southern parts of the United States, firefly experts and aficionados feel excited, but also a bit frantic. The adult flight period of most firefly species lasts just a matter of weeks, and the phrase that often comes to mind is, so many sites, so few nights! Each year we are presented with brief windows of opportunity to learn more about firefly species, but too often we’re constrained by the lack of person power to head out into the night to survey.

This year, I am optimistic that Firefly Atlas participants (yes, you!) will make great strides in expanding and updating our knowledge of North American Lampyridae. Read on for an overview of the types of discoveries we could make.

Fill gaps in distribution maps (and seasonal calendars) for threatened species.

Florida intertidal firefly in the Indian River Lagoon

Despite having one of the largest expanses of mangrove and saltmarsh habitat on the eastern coast of Florida, the Indian River Lagoon has surprisingly few records of the Florida intertidal firefly (Micronaspis floridana). Where are the remaining populations in this environmentally-stressed estuary? This May would be a great time to survey, but this adults and larvae of this species can be found during most of the year.

Keel-necked firefly in the Chesapeake Bay

Just last year, surveyors with Maryland Biodiversity project found keel-necked fireflies (Pyractomena ecostata) on the Eastern Shore of Maryland for the first time. What is this species’ distribution in the Chesapeake Bay? Is it on the Western Shore? We’ll need more Firefly Atlas participants surveying salt marshes on July nights to answer this question.

Cypress firefly in Kentucky?

Photuris walldoxeyi is known to occur in high quality swamp habitats from Mississippi north to near Bloomington, Indiana, but it’s never been found in Kentucky. Does Kentucky have cypress firefly populations? Someone should go check between mid-May and mid-June!

Check out our Wanted Posters for some other ideas of species to look for!

Get to know them all! Make a dent in data-deficiency.

In 2021, conservation assessments of North American firefly species found that over half of assessed species were data-deficient, meaning that we simply didn’t have enough current information about their distributions, trends or threats to know how they are doing.

Below are a few examples of data-deficient firefly species that are just waiting to be studied.

Cattail flash-train firefly (Photinus consimilis)

Historically, this lightning bug had a widespread range across North America, from Florida north to Ontario and as far west as Oklahoma. However it’s unclear what its current range is, and as a wetland specialist it can’t live just anywhere. It was found to be data-deficient in the 2020 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species assessments. Mapping out current populations will be the first step toward better understanding the conservation status of the cattail flash-train firefly.

Punctate firefly (Photinus punctulatus)

Named for the pitted texture of its pronotum (headshield), Photinus punctulatus is a species in which the females are brachypterous (short-winged) and unable to fly. This means that if they were to be wiped out in an area, it would be very hard for a population to re-establish itself. There are records of this lightning bug from Texas north to Iowa and Illinois, but no one has paid this lightning bug much attention in a long time! Over sixty years ago, Dr. Jim Lloyd observed Photinus punctulatus near New Salem State Historic Site in Petersburg, IL. Is the species still there? Someone should find out!

Microphotus glow-worm fireflies of the Southwest

Tiny and mysterious, Microphotus glow-worm fireflies manage to live in harsh, arid environments in the southwestern United States. During the summer, glowing flightless females may be spotted on low perches near their burrows and males occasionally show up at moth lights. We know very little about these insects, and five of the six Microphotus species are considered data-deficient.

Wondering what data-deficient species are in your area? Use this species checklist, entering “DD” under Red List Category and selecting your state under Distribution.

Help us get better at counting lightning bugs

Counting fireflies or estimating their abundance can feel like an impossible task. This has made it difficult for scientists to study trends in firefly populations and to measure the response of fireflies to stressors (like pesticides and light pollution) and land management activities (prescribed fire, vegetation management, and habitat restoration).

If you are a land manager or biologist interested in monitoring a firefly population that you manage, we could use your help testing firefly index of abundance protocols. This might look like taking a series of long-exposure photographs of firefly displays, doing transect counts of glowing firefly larvae, or setting out glowing LED traps to capture (and then release) male glow-worm fireflies.

Please reach out to Richard and Candace at [email protected] if you’d like to test and refine firefly counting techniques.

Enjoy the magic!

We hope you have a fantastic lightning bug season with lots of learning and moments of awe. Thank you for contributing to our collective knowledge of fireflies and to their conservation.

Remember, the Firefly Atlas has several resources that you can turn to as you become your area’s local firefly expert: